The fundamental gap between image measuring instruments and traditional gear measuring tools stems from their fundamentally different technical philosophies: one acquires holistic information through “observation” for digital analysis, while the other verifies specific, critical dimensions through “contact.” This underlying difference in logic results in significant disparities in efficiency, capability scope, and applicable scenarios.

I. The Revolution in Measurement Methods

-

Traditional tools are like possessing a set of specialized “single-function inspection tools.” For example, a pitch micrometer is dedicated to measuring pitch length, a pitch gauge specifically checks pitch error, and a runout tester exclusively evaluates the accuracy of mounting references. Each measurement is independent and isolated. To comprehensively evaluate a gear, operators must use multiple instruments, performing dozens or even hundreds of repetitive operations and recordings. This cumbersome process is akin to “seeing the tip of the iceberg through a tube, piecing together a picture from scattered points.”

-

In contrast, an image measuring system functions like a “full-body CT scan.” It places the entire gear (or critical sections) within its visual field, rapidly capturing complete contour images via high-resolution cameras. Subsequently, all dimensional, shape, and position measurements are automatically performed by software on this digitized “image.” It instantly acquires all geometric information of the measured area, achieving “complete transparency.”

II. Efficiency and Level of Automation

-

Traditional tools rely heavily on the operator's skill and experience. Each zeroing, each reading, and each probe movement can introduce human error. The measurement process is time-consuming, with data recorded by hand or manually entered into computers. The entire workflow is labor-intensive, inefficient, and ill-suited for high-volume inspection.

-

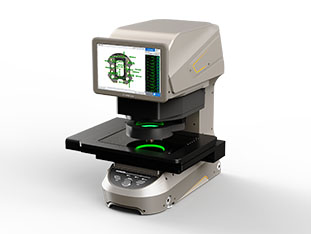

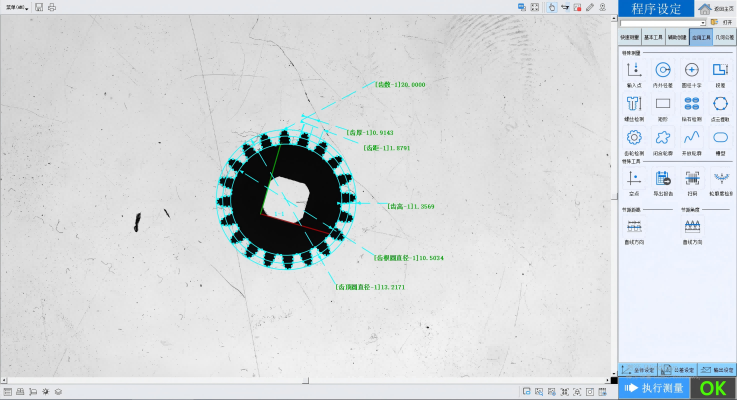

The core advantage of image measurement systems lies in automation and high throughput. Once programmed, operators only need to load and unload parts, then click the “Start” button. The instrument automatically completes the entire process: capturing images, edge detection, calculations, and report generation. Measuring dozens of parameters can take less time than measuring a single parameter with traditional tools. This not only significantly reduces labor requirements but also ensures inspection cadence aligns with modern production rhythms.

III. Information Dimension and Data Depth: Two-Dimensional Features vs Three-Dimensional Profiles

-

Traditional tools excel at capturing specific critical parameters of gears. These parameters are core indicators defined by standards to control gear functionality, with direct and reliable measurement results. However, the information they provide consists of isolated points or lines, failing to intuitively reflect overall profile shape errors (such as profile bulging or concavity) and making complex traceability analysis more challenging.

-

Image measuring instruments excel at comprehensive, contour-based analysis. They not only measure all two-dimensional dimensions accessible to traditional tools (such as pitch circle diameter, root circle diameter, tooth thickness, etc.), but also effortlessly perform contour evaluation, positional evaluation, and specialized gear analysis like tooth profile and tooth direction analysis. More importantly, it generates complete, visual contour data, including deviation color maps that make problem areas immediately apparent. This provides robust data support for process improvement.

IV. The Dialectical Relationship Between Precision and Applicability

-

Traditional tools can still deliver very high, even top-tier precision in their specialized domains. For on-site inspection of large-module, oversized gears, or final arbitration measurements of certain ultra-precision machined gears, contact measurement remains irreplaceable at times due to its direct operating principle.

-

The accuracy of image measuring instruments is constrained by optical systems, lens distortion, lighting conditions, and workpiece surface quality. Gears with reflective, dark, or transparent materials require special treatment for precise measurement. Furthermore, these instruments inherently focus more on two-dimensional and 2.5-dimensional measurements. For strictly three-dimensional complex surfaces, their capabilities may fall short compared to specialized coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) or gear measuring centers.

Product recommendation

TECHNICAL SOLUTION

MORE+You may also be interested in the following information

FREE CONSULTING SERVICE

Let’s help you to find the right solution for your project!

ASK POMEAS

ASK POMEAS  PRICE INQUIRY

PRICE INQUIRY  REQUEST DEMO/TEST

REQUEST DEMO/TEST  FREE TRIAL UNIT

FREE TRIAL UNIT  ACCURATE SELECTION

ACCURATE SELECTION  ADDRESS

ADDRESS Tel:+ 86-0769-2266 0867

Tel:+ 86-0769-2266 0867 Fax:+ 86-0769-2266 0867

Fax:+ 86-0769-2266 0867 E-mail:marketing@pomeas.com

E-mail:marketing@pomeas.com